In September I visited Oklahoma at the invitation of Kristen Oertel, a historian at the University of Tulsa who had received a Mellon Foundation grant to host lectures and courses on historical trauma and healing. The event was a partnership between that university project and the John Hope Franklin Center for Reconciliation, a community organization. The program was beautifully conceived by Kirsten and her colleagues, and by the John Hope Franklin Center’s Outreach and Alliance Director, Vanessa Adams-Harris. (For those of you in Afro-Native Studies: Vanessa told me that she is “Aunt Vanessa” to the independent scholar Darnella Davis, author of Untangling a Red, White, and Black Heritage.) Old friends and new colleagues from the Cherokee Nation attended. (Much of my early research focused on slavery, race, and gender in Cherokee history.) This was both a surprise and a joy for me. Musicians performed songs from both West African and Cherokee and Muskogee traditions. I had the pleasure of re-meeting residents who had attended the launch of my revised and augmented novel, The Cherokee Rose, at the Black Wall Street Legacy Festival in 2023.

As much as I appreciated the event itself, a highlight of my trip was time spent outside on the city streets. Each time I visit Oklahoma, I am struck by how multifaceted it is. I never quite know if Oklahoma is southern, midwestern, or western, and in historical reality and lived reality, it exists in all these regions simultaneously. There are western hats and boots aplenty, along with soul food and barbeque joints. Oklahoma is at once “Indian Territory,” Black space (as the western state that had the second largest enslaved population before the Civil War), and central to Euro-American settlers’ westward movement (through the Land Run of 1889). One could even say that a larger story of the nation could be told through the lens of Oklahoma. The streets of Tulsa hold the memory of all this history.

Vanessa Adams-Harris drove me through the historic community of Greenwood (or Black Wall Street), the district destroyed by the Tulsa race massacre of 1921, pointing out the boundaries on all four sides. She wanted me to see how vast the area was and to notice how white and black neighborhoods of the early 20th century had been separated by single streets. These racially segregated communities shared a spatial intimacy that, to Vanessa, held specific meaning. She pointed out that people committing violence and people suffering from violence were virtual neighbors who would have known each other before the tragedy; victims who survived would have been aware of their attackers moving freely through town after the tragedy. She also wanted me to see a sole building that had been standing during the event – an abandoned brick industrial structure that the city has yet to repurpose. She called this a “witness building,” a term that I found haunting and effectual.

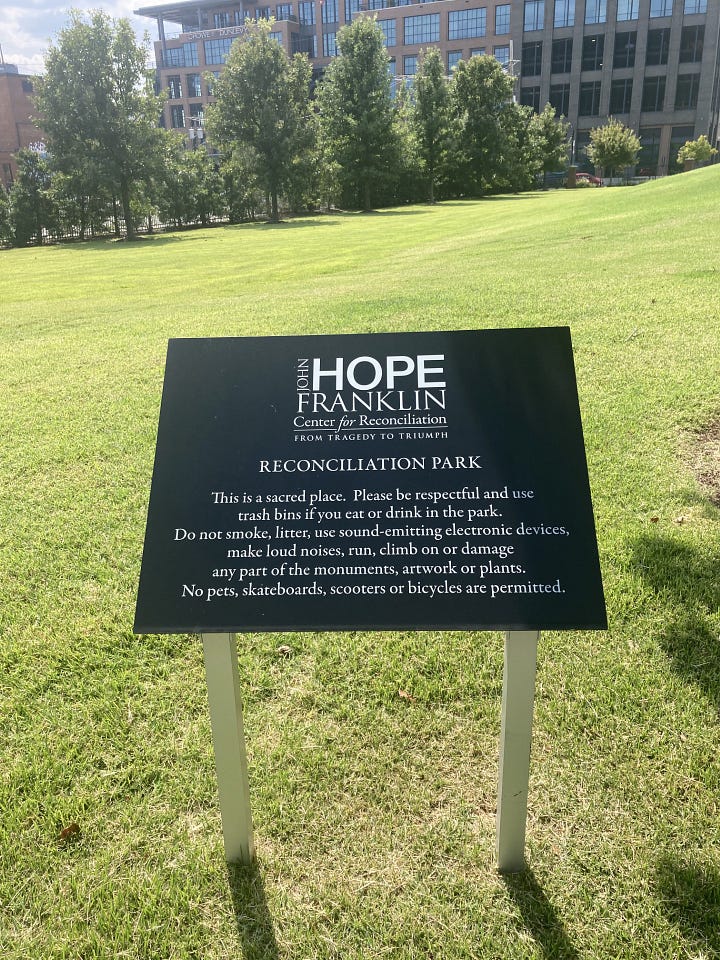

While in Tulsa, I spent an afternoon in the John Hope Franklin Reconciliation Park, which is located within the historic boundaries of Greenwood. (After my lecture, I met the widow of the park’s creator, who described how she midwifed her spouse’s dream as he developed it over many years.) This park was, to my eye, a major contribution to public space and community identity in Tulsa. It is serenely green, full of statuary, rich with historical explanation about Indigenous peoples and Black peoples, and bordered by a soothing wall of falling water. A sign proclaims the land as “sacred.” A “healing path” invites visitors to walk among shrubs and flowering plants. As I read a detailed account of the Tulsa massacre arranged across several large markers, I couldn’t help but cry. I found the path tucked away within rows of shrubbery and let my emotions spill out while observing other people in the park. They appeared to be from various racial and cultural backgrounds – white, black, perhaps Native American. Some were walking; some were meditating. One woman gave me a smile. I took comfort in their collective presence, feeling that we need more areas like these in our cities that invite people to informally share “sacred” space.

During my walk to the park, I crossed railroad tracks where a concrete construction barrier had been spraypainted with the word “Love.” This struck me as profound. The declaration was artful against the backdrop of a bleak street scene. Then the “Love” note overlapped in my line of sight with a “Utility Work Ahead” sign, and the messages connected.

The big election is just over two weeks away. Our country is facing hard times that will surely make the history books of future generations. We have work ahead to restore our values and democracy. And in that work, love is a public utility – an essential shared resource and common good.

-Hey, did you know that my novel, The Cherokee Rose, is a ghost story set in Georgia and Oklahoma? If you’re looking for a Halloween read that is enjoyable (romance meets mystery) as well as illuminating about Cherokee history, Afro-Indigenous genealogies, and the search for family histories, check it out!

-Where is Tiya’s Substack editor, you might be asking right about now. She is still focusing on her real job at a university press. But here’s a drawing she made for fun of the main characters in The Cherokee Rose.

-In October I’m often asked to do interviews and podcasts about haunted places because I published a book called Tales from the Haunted South in 2015. (Exciting news from the University of North Carolina Press: that book will come out in audio soon!) I’ll share the podcasts on my website, so stop by there to listen if you’re interested in ghost lore and public history.

-Congratulations to Victor Luckerson, whose immersive book, Built from the Fire, about Tulsa’s Greenwood district, just won the Museum of African American History’s Stone Book Award! Victor recounts the history of the area before, during, and after the attack, highlighting how residents rebuilt their community.

Beautiful. The title is so good. It captures so much.

Beautiful. I’m moved by your story — a sacred space heightened awareness and connected to an epiphany in humble, easily overlooked surroundings. 💚