I want to share an inkling about Harriet Jacobs, as I have heard from a reader here that such a post would be welcome. But I confess to having a dilemma. When I last spoke about Jacobs around two weeks ago, I did not write my comments down. In addition, something odd happened at that church affair in Jacobs’s honor where I had not expected to be speaking.

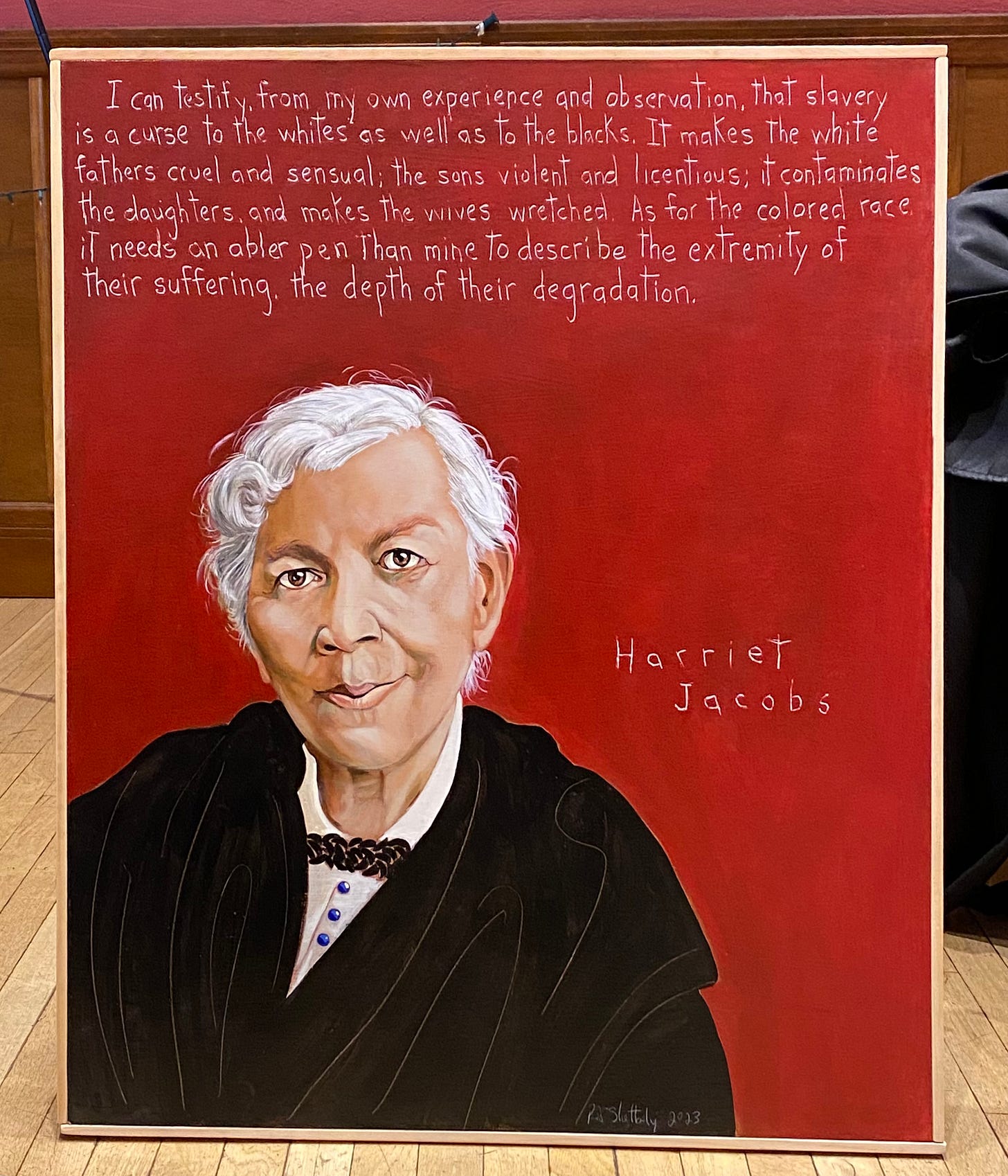

I was drawn into this event by a local pastor, the Reverend Dan Smith, who stewards First Church in Cambridge, teaches a class on preaching at the Divinity School here, and served on the Harvard & the Legacy of Slavery Committee. Dan Smith and his congregation wanted to honor Jacobs along with other historical figures with ties to the history of their congregation (one of the first established in Cambridge in the 1600s) or to the city. Dan commissioned a new portrait of Jacobs from the artist, Robert Shetterly, whose series Americans Who Tell the Truth has captured the likenesses of over 260 historical and contemporary figures. First Church was hosting an unveiling of the Jacobs portrait along with an exhibit of other “truth tellers.”

Dan asked me to speak about Jacobs along with the Divinity School dean Melissa Bartholomew, and the portraitist Robert Shetterly. I was in the middle of a mind-bogglingly busy semester and just returning from a research trip. I told the reverend that while I would be happy to attend, I could not commit to giving remarks. But the night before the event, I awoke with words about Harriet Jacobs unspooling in my mind. It was as if a talk had begun writing itself as I slept. The next morning, I emailed Dan to say I thought I should share a few words.

I wish there were a recording of all that was said during the unveiling ceremony for Harriet Jacobs’s portrait. I wish I had notes to crib from now as I draft this post. Every person who spoke that day seemed to open an invisible door wider, allowing the light of Jacobs’s wisdom to shine in. While Dan Smith was describing Jacobs in his introductory remarks, her portrait lurched off the pedestal, emitting a boom. The room fell silent. Melissa Bartholomew, seated next to me in the panelists’ row of chairs, said “Jacobs is here. She’s here.” There can be any number of explanations for the portrait’s spatial shift in that moment, having to do with coincidence or physics. I do not mean to discount those, but neither will I discount Reverend Bartholomew’s assessment of the case. The artist and church members rushed forward to resettle the portrait on the stand, and the program continued through the shock while being irrevocably altered by it. Dan Smith completed his introduction. Melissa Bartholomew offered a stirring commentary on Jacobs’s narrative as “scriptural” text. I spoke next, and here is where my nonexistent notes fail me.

I let the words from the night before re-assemble and catch voice, and the rest is nearly a blur. I said something about the unique contributions of Jacobs’s text to the slave narrative literary genre, about the intricate (and excruciating) escape she executed, about her identity as a mother, about her desire for a home where her family could be safe, and about how she finally (if fleetingly) found that homeplace in Cambridge. I also said something like -- in the face of extreme challenge, Jacobs had become a navigator of change. (Here, I insert a nod to the historian Nancy Shoemaker, whose edited collection on Native American women, Negotiators of Change, surely echoed in my mind as wrote that last sentence.) I presented Jacobs as a navigator of change because she escaped enslavement when an awful shift in her circumstances demanded it. Then, after absconding from bondage in North Carolina and evading recapture in New York while working as a domestic, she penned a political text to expose the evils of slavery. She weathered the Civil War while returning to the South to serve as a relief worker and teacher for African American refugees. She moved repeatedly over the ensuing decades, remaking home in difficult situations, crafting a brave memoir, and offering shelter, care, and tutelage to others in need. She lived through one of the most tumultuous periods in American history and emerged as a change maven.

At First Church that Sunday, I emphasized this quality of Jacobs to meet change head-on and suggested that in our uncertain times, we should take her example. I said we often concern ourselves with pushing progressive social change (a worthy endeavor) but that we should be just as concerned (if not more so in this rapidly destabilizing moment) with adapting to change. We must create and sustain local communities that can withstand (and even anticipate) change that is happening at the rate of “exponential time” (and here, I borrow a phrase from a recent episode of The Ezra Klein Show, “My View on AI”). The COVID-19 pandemic revealed an urgent need for us to develop our adaptive capacity. And it would seem, that with storms raging and banks failing, this is just the beginning of our societal and global test. The shocks are likely to keep on coming. Harriet Jacobs’s narrative is an account of one woman’s answer to drastic disruptions that do not abate. Moving forward means looking inward to assess our resources for resilience.

Harriet Jacobs is enjoying a cultural renaissance now, a renewed and growing attention to her life and work. In 2021, I taught a Zoom seminar in which students read Incidents and considered the state of Jacobs’s former boardinghouse in Harvard Square. Along with the teaching fellow for that course, Alyssa Napier (a recent graduate from the School of Education and current editor in various domains, including this Substack), I typed notes for a Loopholes Project that would attend to Jacobs’s existing house(s) in Cambridge and other historic sites and stories related to her legacy. A junior in that class, Kyra March (soon to be a student in a History PhD program) was inspired to write a senior honors thesis that treated Jacobs’s extant homes within a broader analysis of Black women’s house museums (or the lack thereof). In 2022 Melissa Bartholomew taught a Divinity School seminar in which students slowly read Incidents. (At least one recent college seminar elsewhere that I pulled up via a Google search has focused solely on Jacobs as a subject, and there are likely more.) In 2020, I was asked to write a preface for a new edition of Incidents for the Modern Library Torchbearers Series from Penguin Random House. A new annotated version of Incidents, edited by Koritha Mitchell, will be out in spring 2023 from Broadview Press.

In Cambridge, a grassroots Harriet Jacobs Legacy Committee formed in 2022 by local organizer Nicola Williams aims to commemorate Jacobs and promote the protection of her historic boardinghouse on Story Street. Around that same time, a group of Black women artists and scholars hosted a gathering in Italy named for Jacobs’s famous phrase, “A Loophole of Retreat.” Meanwhile, in North Carolina, the director of the state’s historic sites, Michelle Lanier, has launched a series of commemorative events, including a 2023 reading from Incidents on the courthouse steps where Jacobs’s grandmother, Molly Horniblow, gained her freedom.

Why Jacobs? And why now? Harriet Jacobs was many things: writer, survivor, mother, defender, homemaker, and seed-bearer. She was also a model for facing into the headwinds of change.

What a wonderful post! "Incidentes in the Life of a Slave Girl" was a foundational text in the African American Literature course I took with the marvelous Professor John Ernest during my Master's Program at Sewanee. It deeply impressed me on many levels. Who can forget her seven years lives in her grandmother's attic? How she was basically crippled when she finally emerged? Her spirit was (is?) strong. I am absolutely sure she was there with all of you. Wonderful.

Wow, the serendipity! I've been working on a poem about Cambridge and just performed the first draft last night, before I read this post when I woke up this morning. I can't not share the following passage. (Context: the poem is centered on the Alewife/Fresh Pond area, and at this point I'm reflecting on the garish new developments business and housing developments underway by the train station.)

with the implosion of the post-2008 monetary

regime and now bank runs on the engines

of this bubble of obnoxious tech start-ups I wonder if

it will all just fall apart and then the cops can stop

doing their sweeps Jackal told me about along

the adjacent scenic bike path where I’ve seen

them harassing people under bridges

and the offices and labs and condos can be taken over

but for now the place is cursed, either cursed

or haunted, Rianna told me there’s a difference

people said cursed when someone crashed their car

into a concrete block on top of the T station

shattering the ceiling of the atrium and raining glass

down on people below and the cops said

it was intentional?, I never found out what that

was all about but with all the mess on the T

and also that big crash right outside

the station that took out a utility pole

cursed seems like the word, I felt bad

for spooking Rianna with all my talk of ghosts

I didn’t know she believed in them like that

I explained I don’t think they throw chairs and shit

but that I believe in them in another way, in the way

good historians in places like this believe in ghosts

maybe Tiya believes in ghosts like that

she lives in town, I think she’d get it

in the sense that there’s a memorial

on my block for the veterans of the

Spanish American War with a seal

depicting a woman on her knees

opening her arms to two Yankee rescuers

and clockwise around the seal it reads

Phillipine Islands - Cuba - Porto-Rico

U. S. A.

the statue is called The Hiker, one of fifty

copies that measure the continent like a map

which made it useful for a 2009 study

on the effects of air pollution